Shoulder to shoulder, they stand in prayer. Khadija and Halima, both dressed in long cloaks, hands folded on their chests. Their hijab covered heads are tilted downwards as the words of prayer wash over them. They raise their hands in unison for dua, then turn and share a soft hug and smile, saying “Jummah Mubarak.”

Khadija picks up her shoes and walks home. She stays at the student accommodation near campus. She puts on her waitress uniform and goes to work. Khadija thinks about how little sleep she’s going to get tonight, because she still has an assignment to finish, and she’s working all weekend. All her family’s savings, and hopes, have been invested in her obtaining this degree. But she still has to work to fund it, and self-motivation isn’t cheap. It’s her final year, the final push.

Halima heads home too, to pick up her books, before heading to the library. She’s determined to study hard and finish this degree with excellence. She knows her parents are planning her marriage, but she’s not ready yet. She wants to get her degree and find a good job first. All her parents’ hopes of grandchildren are invested in her, as an only child. But she wants to flourish on her own too, and self-motivation isn’t cheap. It’s her final year, her final push.

On Monday, a yawning Khadija has a meeting with the university’s finance officer. She has defaulted on her fees payments, and even if she passes her exams, she won’t get her degree until she pays up. Khadija’s heart sinks deep into her stomach. How is she going to tell her parents that their life savings weren’t enough?

Halima also has a meeting, with the desk of her faculty. Her marks have slipped, and if she’s careful, she might not graduate at all. Halima’s heart sinks deep into her stomach. Her parents have told her that if she doesn’t finish this year she’ll be married off. Her husband can provide for her. She finds in herself new resolve to achieve her goals. How will she tell her parents that she wants her independence?

Khadija hears whispers of Fees Must Fall and stops to listen. They want to shut down the university until education is equally accessible to everyone, regardless of financial situation. Khadija finds herself agreeing, the years of pent up frustration at having to simultaneousltly work and study exploding into her march as she picks up a placard.

Halima hears whispers of Fees Must Fall and stops to listen. They want to shut down the university, even if it means preventing exams from taking place. Halima panics, knowing that if it happens, her entire life could go down a path she is trying to desperately to escape.

Khadija marches with the crowd through the city. She looks at the fires around her, watches as protesters throw rocks at the police and stun grenades are fired back. This violence, this is not what free education is about. She hangs back with the majority of students, demonstrating their peacefulness by standing still, but still firm in their demand for access to education. Khadija feels that the protest is justified based on the exclusion she experiences the to finances. Protest is her right as a citizen.

Halima watches the fires burn on TV, as the students toy toy through the streets. She feels tears welling up in her eyes as the vice Chancellor of the university makes a press statement declaring that universities will close indefinitely if the protesters don’t stop. Her mother tells her to get ready, stop watching TV, the boy is here to see her! Halima feels that the protest is preventing so many hardworking people from reaping the benefits of the countless hours spent studying. Dissenting is her right.

Friday comes, and the adhaan echoes, calling worshippers to prayer. Khadija and Halima pray side by side, both finding tears slip out as they wonder about their futures. They turn, seeing each other’s tears and comfort each other in an embrace. Out through the mosque doors they walk, and become strangers once more.

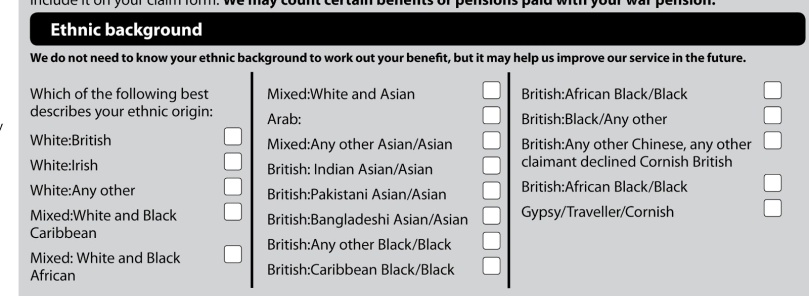

How could I, someone from Africa, look so much like her, someone born in India and living in England?

How could I, someone from Africa, look so much like her, someone born in India and living in England? And thinking, I fit in none of these boxes.

And thinking, I fit in none of these boxes.